Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is recognized as the most prevalent congenital infection worldwide, impacting an estimated 0.7% to 1% of all live births. Despite its substantial global burden, there remains a considerable lack of awareness about CMV and its potentially severe outcomes among both the public and healthcare professionals. Approximately 11% of infected neonates are symptomatic at birth, with a significant risk of 30% to 40% developing long-term neurological sequelae, including conditions like sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL), cerebral palsy, vision impairment, and growth retardation. The economic toll of these sequelae in the United States alone is estimated at $2 billion annually. Historically, the absence of effective treatments meant that universal screening for CMV in pregnant women was not deemed justifiable; however, this perspective is evolving with the advent of promising antiviral therapies.

CMV is an enveloped DNA virus from the herpes family that establishes a lifelong latent infection after primary exposure, residing primarily in monocytes and granulocytes. Vertical transmission can occur through a primary maternal infection (MPI), the reactivation of a latent virus, or even reinfection with a new CMV strain. The virus spreads via direct contact with contaminated bodily secretions, such as urine, saliva, genital fluids, and breast milk. The most significant risk factor for maternal infection is exposure to young children (under two years old), who are known to shed the virus in their saliva and urine for extended periods.

Epidemiological data indicate a high global CMV seroprevalence, with rates of 83% in the general population and 86% among women of childbearing age, even reaching 90% in regions like Brazil. Seroprevalence is notably higher in populations with lower socioeconomic status and in developing countries, which contributes to increased rates of congenital CMV resulting from non-primary infections. While MPI carries a higher intrinsic risk for vertical transmission (approximately 30-40%) and more severe congenital infection, the majority of infected newborns globally are actually born to mothers with pre-existing immunity (non-primary infection), reflecting the high baseline seroprevalence. Vertical transmission rates in MPI vary substantially by gestational trimester, ranging from 20-30% in the first trimester to as high as 72% in the third trimester.

Maternal CMV infection frequently presents with minimal or no symptoms in immunocompetent individuals. However, in immunosuppressed individuals, including the developing fetus, uncontrolled viral replication can lead to viremia and widespread organ involvement, causing conditions such as pneumonitis or hepatitis. The intricate pathophysiology of CMV infection during pregnancy involves direct viral infection of placental cells, which can impair placental development and function, as well as indirect damage mediated by the immune system. These processes can result in adverse outcomes including miscarriage, preterm birth, and fetal growth restriction (FGR). Fetal susceptibility to infection appears to increase with advancing gestational age, possibly due to the ongoing differentiation of cytotrophoblasts.

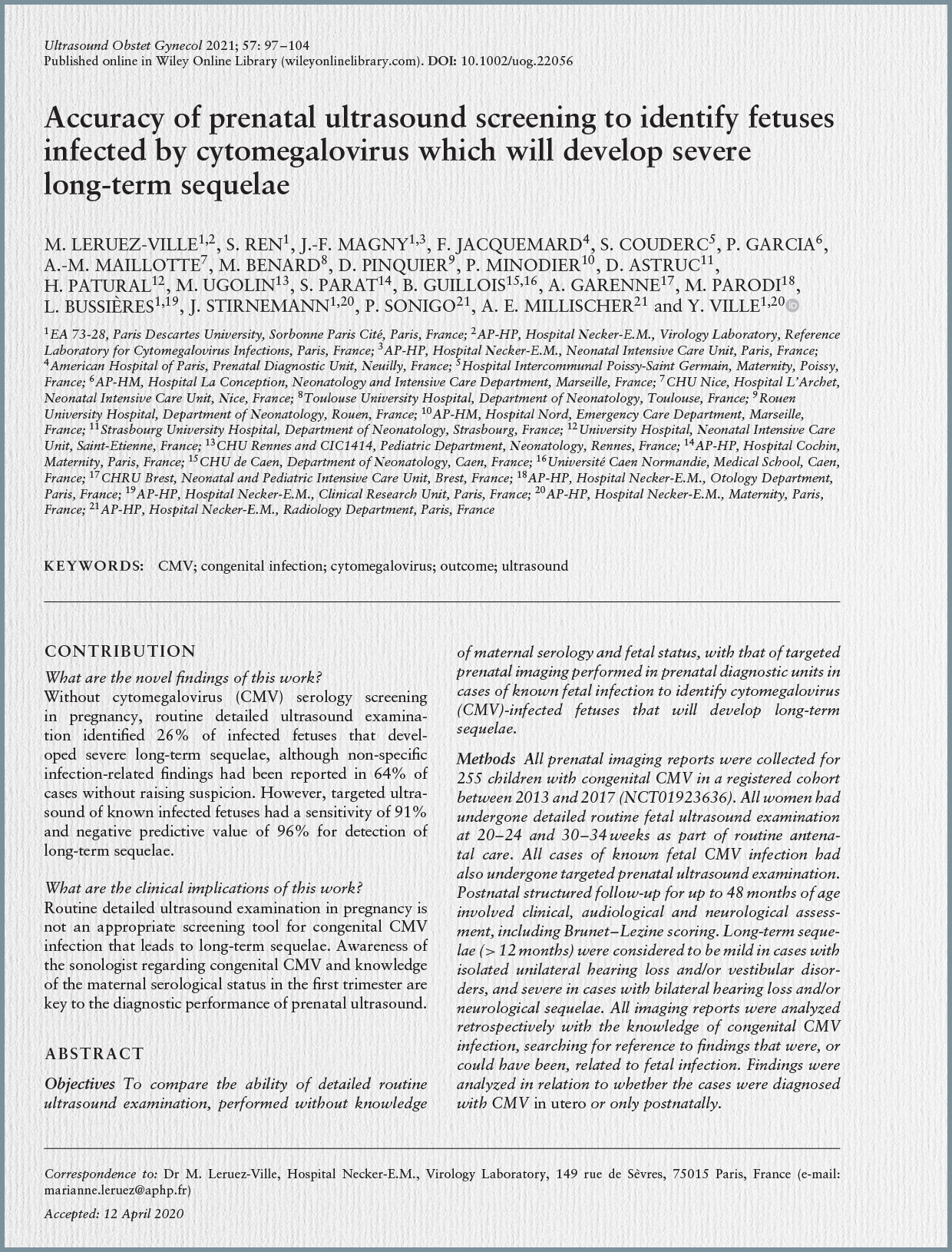

Fetal disease, when present, is typically progressive. Initial ultrasound findings often reflect systemic infection, manifesting as FGR, abnormal amniotic fluid volume, placentomegaly, or hepatic calcifications. Central nervous system (CNS) abnormalities usually appear later, and severe brain involvement is a critical predictor of poor prognosis. Microcephaly, in particular, is identified as the sole ultrasound finding that consistently predicts an unfavorable outcome, with a high predictive value of up to 95%. Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) serves as a valuable adjunct to ultrasound, capable of revealing subtle abnormalities, especially in CNS, that might be missed by ultrasound, particularly in cases of first-trimester infection. Conversely, the absence of CNS abnormalities on both prenatal ultrasound and MRI is associated with a good prognosis. Infected newborns can present with a spectrum of clinical signs, including jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, petechiae, thrombocytopenia, microcephaly, and abnormal brain imaging.

The diagnosis of CMV infection in the fetus is primarily established through CMV polymerase chain reaction (PCR) performed on amniotic fluid, considered the gold standard. Amniocentesis for this purpose is recommended after 21 weeks’ gestation and at least 6 to 8 weeks following documented maternal infection to minimize the risk of false-negative results. For newborns, diagnosis involves viral detection via PCR in urine or saliva samples collected within the first three weeks of life, with saliva noted to contain 10 times higher viral copies than urine.

In terms of prognosis, the review emphasizes that fetal abnormalities and long-term sequelae are predominantly linked to maternal primary infections acquired during the periconceptional period or the first trimester of pregnancy. While vertical transmission rates increase with advancing gestational age at the time of maternal infection, the risk of severe fetal insult significantly declines after the first trimester. Key predictors of poor neonatal prognosis include a high fetal viral load (>30,000 copies/mL) and a low platelet count (<50,000/mm³) in cord blood, alongside the presence of microcephaly on imaging. A negative amniocentesis result is highly reassuring, indicating a very low risk of severe symptoms or neurological sequelae, even if the newborn’s urine later tests positive for CMV. Long-term sequelae can affect both symptomatic (40-60%) and asymptomatic (approximately 13.5%) congenitally infected children, with SNHL being the most common, often progressive and sometimes late in onset. Other potential sequelae include vision loss, intellectual disability, and developmental delays.

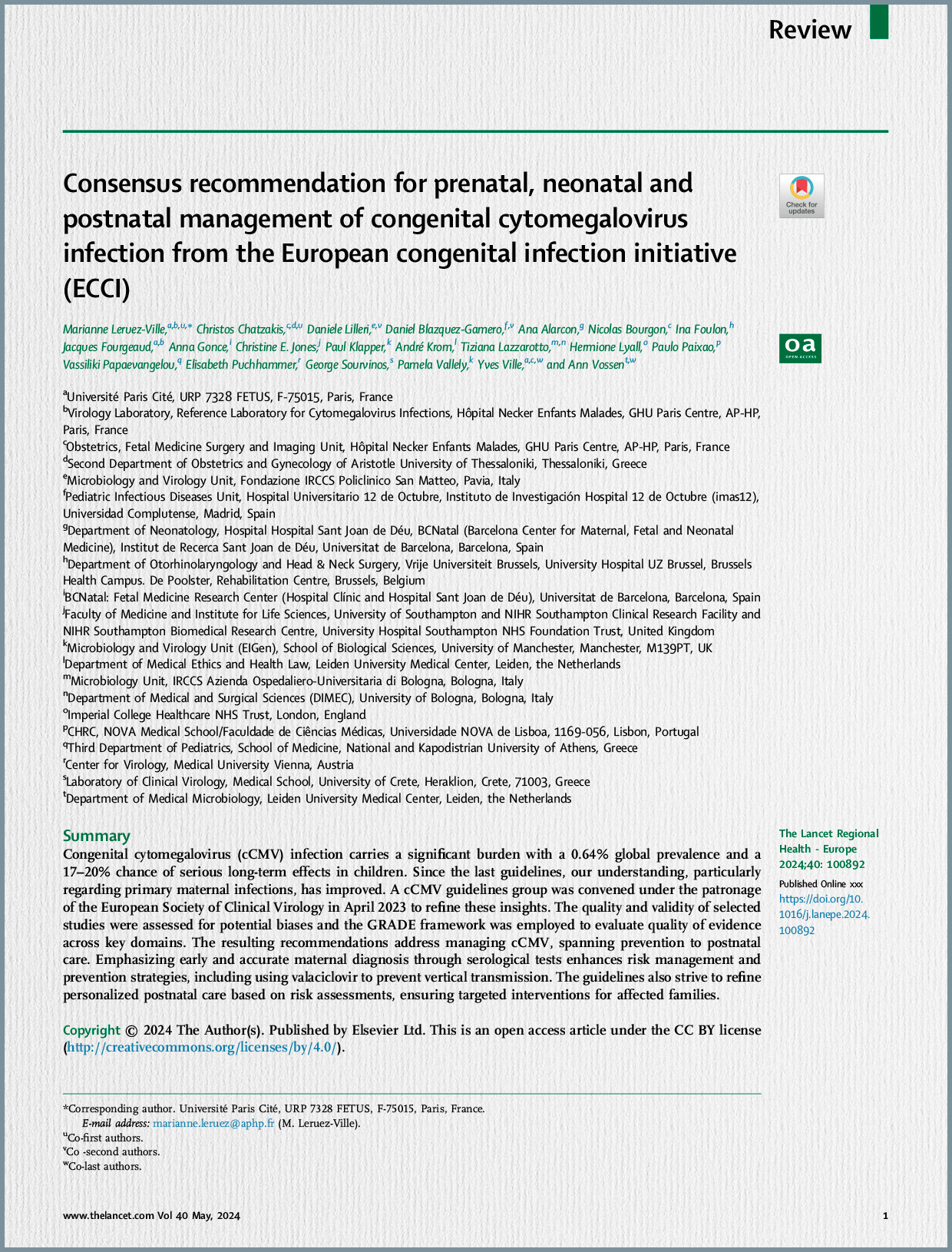

Regarding prevention, there is currently no licensed CMV vaccine available, although ongoing research efforts are deeming it a high priority. Behavioral interventions, such as stringent hygiene practices, have shown some promise in reducing infection rates but face challenges related to maternal adherence and a general lack of widespread awareness campaigns.

The management of CMV infection during pregnancy has significantly evolved. While potent antivirals like ganciclovir are effective in non-pregnant adults, they are not approved for use in pregnancy due to toxicity concerns. However, valacyclovir, an acyclovir prodrug, stands out as the most promising medication for preventing congenital CMV infection after maternal primary infection in early pregnancy. Clinical studies, including randomized controlled trials, have demonstrated that high-dose oral valacyclovir (8 g/day), administered from the diagnosis of MPI in early pregnancy until amniocentesis, can significantly reduce the rate of vertical transmission by up to 71%. This treatment generally exhibits a favorable safety profile, with rare and reversible side effects such as acute renal failure. Although some studies propose continuing valacyclovir until delivery to prevent late transmission, this approach lacks support from prospective randomized trials. Conversely, the use of human hyperimmune globulin for preventing vertical transmission is largely not supported by current evidence.

For symptomatic newborns, ganciclovir is the drug of choice, administered intravenously, typically for 42 days. It has shown substantial benefits in promoting neuropsychomotor development and reducing the incidence of hearing loss. Valganciclovir, an oral alternative, is also discussed. Treatment is recommended for newborns presenting with CNS involvement, isolated hearing loss, or severe manifestations such as persistent hepatitis or thrombocytopenia.

In conclusion, the review stresses that the historical reluctance to implement universal CMV screening during pregnancy, often attributed to the absence of effective therapeutic options, must be re-evaluated. Given the robust evidence supporting the safety and efficacy of valacyclovir in reducing vertical transmission following early maternal primary infection, the article advocates for amending current guidelines to incorporate CMV screening during the periconceptional period and the first trimester. Early diagnosis is paramount to facilitate timely interventions and mitigate the severe, long-term consequences of congenital CMV infection.